Architectural Replicas

- Tim Boatswain

- Jul 8, 2025

- 2 min read

Updated: Jul 9, 2025

I recently read an article by Elizabeth Kostina, entitled, The Replica and the Original Architectural copies of lost structures require reckoning with history and heritage. At what cost is the past rebuilt? ( https://aeon.co/essays/from-rebuild-to-replica-architecture-has-a-double-life) This article got me thinking about the value of architectural copies of lost structures.

The reconstruction of lost architectural structures can be a complex negotiation between historical fidelity, cultural memory, and contemporary values. If you think about it, the cost of rebuilding the past is not merely financial—it involves ethical, political, and philosophical considerations about authenticity, identity, and the purpose of preservation.

Rebuilding lost monuments—whether Warsaw’s Old Town, Dresden’s Frauenkirche, or Beijing’s Yongdingmen Gate—raises questions about what constitutes "original" heritage. A replica, no matter how precise, remains a new object embodying modern intentions. Does it honour history, or "does it risk turning trauma into spectacle?"

Reconstruction is often driven by nationalism, tourism, or collective healing, but selective rebuilding can distort history. For example, Russia’s restoration of Tsarist-era churches contrasts with its neglect of Soviet modernist architecture. Similarly, China’s replica cityscapes sometimes prioritise mythologised pasts over uncomfortable histories.

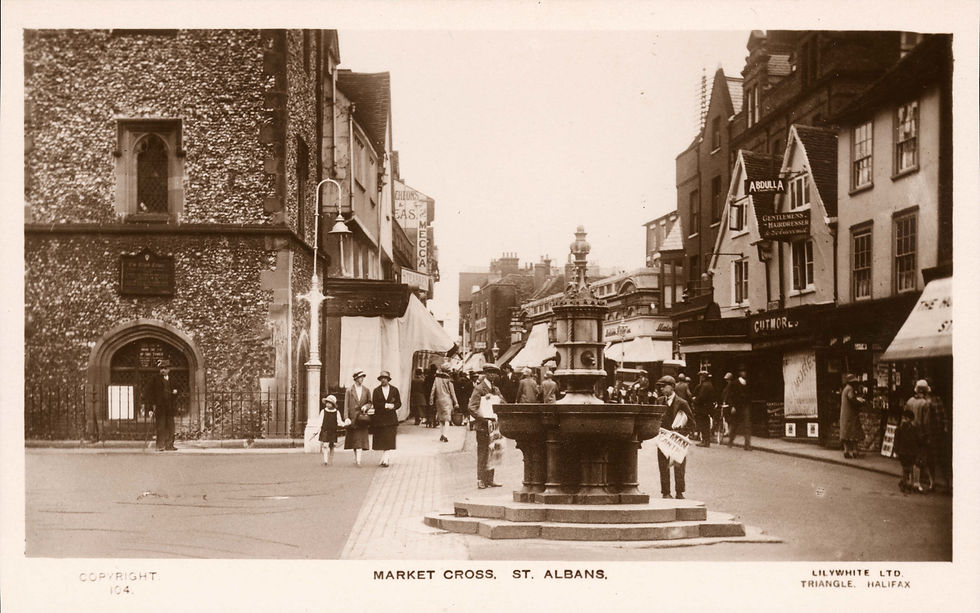

When lost structures are rebuilt as sanitised tourist attractions, they can erase the layers of conflict that shaped them. The Palmyra Arch, digitally reconstructed after ISIS’s destruction, became a symbol of resistance—but also a politically charged avatar, detached from its archaeological context. I have been suggesting that Mrs Worley's Fountain, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott, be returned to its original site in Market Place, St Albans. Mrs Worley's father was Joseph Timperon, who made his money out of slavery. From his will, we know he left an annuity to his daughter Isabella Charlotte Worley. I believe it would be important to acknowledge that the funding for this fountain might have come from a tainted source.

Some argue that voids—like Berlin’s empty Holocaust Memorial or the deliberately unrestored ruins of Coventry Cathedral—can be more powerful than reconstructions. They force confrontation with absence rather than offering the comfort of a facsimile.

With advances in 3D scanning and AI, we may soon see even more ambitious rebuilding projects. But the deeper question remains: Should we reconstruct to heal, to educate, or to reclaim? The cost is measured not in stone and steel, but, I would argue, as a historian, in how honestly we engage with the past’s complexities.

Ultimately, rebuilding is an act of interpretation. The past is never truly recovered—only reimagined. The cost is justified only if the new structure serves as more than nostalgia; it should deepen our dialogue with history rather than simplify it.

Comments